Promulgating a Progressive Pantheon Patrick Mickelson

Kevin Starr is a USC Professor of History and an

accomplished writer. His landmark series on California

has received much critical praise and popularity in recent years. He graduated

from Harvard with a PhD of English and American Literature in 1969. As a

professor, he researches California

history and a history of American culture, as well as the developments of urban

societies. He is also a contributing editor to the Los

Angeles Times.

From

the tribes of the sands of early California

to Cecil B. De Mille and his Ten

Commandments, California has

embodied the drive of a society moving towards a zenith. In Inventing the Dream: California through the

Progressive Era, Kevin Starr tracks the history of Southern

California beginning with the primordial days of old and

majestically sweeping into the period of early Hollywood

all the while setting the stage for the progression of Southern

California into a suburban empire. By playing the contrast of ¡§the

California of fact and the California

of imagination¡¨, Starr shows the interplay between dream and reality, focusing

on the California pictured in the

eyes of those who built it and analyzing the path by which those dreams

modulated into imperfect being, but stepping stones towards the California

of present nonetheless. 1

Starr

begins his analysis cleverly guised as narrative by describing the geography of

California at a time where man¡¦s

impact was miniscule and irrelevant. The uniqueness of the coastal regions of California

from the distinctive inland valleys and deserts played a key role in the

establishment of civilization and the migration of peoples here, with Starr

essentially arguing geographic determinism in the cultural roots of California.

After native culture established firm settlements three thousand years ago, the

Spanish arrived in 1535 and created settlements from the south and going north

to the last mission in San Francisco

in 1823. In what would eventually become cities, rancheros aggregated large

expanses of land into single pieces of property¡Xa distinctly Californian

system. As California moved into

the 1880s, previously established Latin roots faded slowly and characters like

Edward Beale handled business centered around these

systems, largely because they were appropriate to the region. Until the 1890s

Starr describes California as a

¡§literary wasteland¡¨ with the exception of the post-Civil war San

Francisco literary movement which included the great

Mark Twain.2 Towards the turn of the century however, words extended

through all mediums, from novels to news publications, with everything of

importance being recorded. It was during this period that the great mythos of California

romanticism was born, epitomized by Helen Hunt Jackson¡¦s Ramona which Starr portrays as the pre-eminent California

novel and references throughout the course of the book as a sort of reference

point. Even as early as this, the regional distinctions that diversify and

enrich California presented and developed within their own circles more or less

independent of the other regions except for the key points of population

influx.

By

the third chapter, the dream becomes more artistic than developmental, and in

many ways is described as less Californian than simply an amalgamation of the

cultures that contribute to California.

Before 1890, California grew

steadily but gradually until that point when it skyrocketed geometrically until

California, and particularly Southern

California boomed with prosperity. Southern California¡¦s minds

stood out as a regional oddity; Charles Lummis, a man

Starr relentlessly mentions to be a Harvard man (a position Starr himself

admires), was an eastern Yankee turned Vaquero author and literary great. He

wrote poetry and sent his books to the likes of Chief Justice Oliver Wendell

Holmes, empathizing with other writers of the eastern United

States consciousness. However, despite the

high-mindedness of the art and the rhetoric, places like Los

Angeles were defined by money more than mythos;

business was key in the sustenance of the city of the

Angels as were the eastern intellectuals who created prosperous business

ventures there. Starr explains the reason for the immigration of the Yankees as

¡§thousands of health-seekers pouring into Southern California¡¨,

whether it be the weather or the perceived quality of

nature of the region.3 Chapter four explains the first outgrowths of

Protestant Pasadena in the Hispanic-Catholic southern California

as the New England community rather than the predominant

heritage of the region. Men like George S. Patton who led the United

States to victory in the pacific were

spawned in white Pasadena, the town

of the upper class, high society folk. The southern California

economy was founded primarily on the export of its produce: orange¡Xrendering

the term ¡§citrus culture¡¨. Once again, the idea of geographic determinism

supports that notion, as the culture revolved around its economy, determined

largely by the arid climate which allowed for the growth of California

Oranges¡Xthe namesake for Orange County.

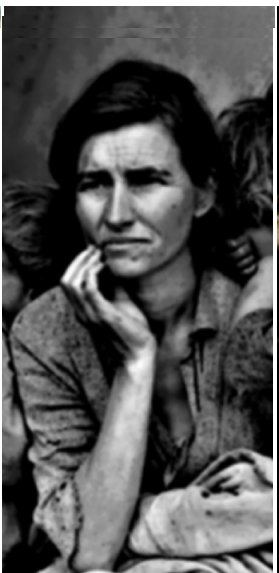

The

most significant section of the book is devoted to the Progressive movement in California.

If the dream of perfection that guided so many incredible individuals was the

fuel, the era of Progressivism was the engine that made ethereality into

reality. The beginnings of the progressive movement lay embedded in the

revolutionary architecture of Arthur Page Brown who coasted on the cutting edge

of San Francisco structure and was

commissioned for hundreds of projects that contributed largely to the economic

and intellectual prosperity of San Francisco.

Many of these projects were transportation based and helped accommodate the

growth of the city with ferry ports to ease access to bay transport. The

progressive elements of chapter seven center around reversing the notion that

California was ruled ¡§by an omnipotent oligarchy and governed by the corrupt

party machines which the oligarchy subsidized¡¨.4 While Progressivism

may have been the American answer to socialism, a small communist community did

exist in Southern California run by Patrick Calhoun and Abe Reef. The disparity

between socialist reform and the current state of affairs was essentially

bridged by this reform and led to the advancements of women, labor, and so

forth. Another important group Starr brings attention to is the

Lincoln-Roosevelt League which actually won many political positions and helped

launch key progressive governor Hiram Johnson into office (who had at the time

had strong links with the Teamsters union). Of most of the reforms, Starr

focuses on the goals of the Johnson California to reform the government linkage

and monopoly of the Southern Pacific railroad company by reigning in some of

the delegated powers it had received through the bedding of business and

bureaucracy. With the movement in

its final days, progressivism began to burn out during the 1910s and between

women¡¦s suffrage and the First World War, was wrapped up for good by 1920.

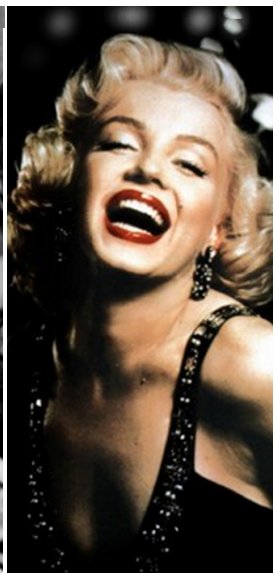

The

final section of Starr¡¦s progressive narrative is the rise of Hollywood

as the greatest asset to not only Southern California,

but also to the world as well. While Hollywood

began as Pasadena did¡Xa small

protestant community¡Xit quickly rose to the top of the economic echelon after

Thomas Edison¡¦s invention of moving pictures. Once the process simplified and

movies could be made by small teams, the possibilities grew endless; soon,

filmmakers D. W. Griffith and Cecil B. De Mille revolutionized simple moving

pictures by creating modern film. Whether it be ¡§Biographs¡¨

by Griffith (or his racist opus The Birth

of a Nation) or De Mille¡¦s sexual comedies,

Hollywood existed by cutting the edge of the social frontier; Starr quotes

Lenin by saying that ¡§the cinema...must and shall become the foremost cultural

weapon of the proletariat¡¨, thus attributing Hollywood the honor of being the

nation¡¦s voice.5 Taking precedence, California represented the

dreams of ordinary people. People could come from the east out to the edge of

the frontier and create their lives anew. Business grew from the sown seeds of

the orange fields and grape vineyards. Ordinary men became extraordinary in the

world viewed through a lens and soon enraptured the whole country¡Xmaking Hollywood

the fifth largest US

industry by 1926. With the rise of Hollywood,

a great deal of anti-Semitism revealed as resistance to the fact that many of

the investors of film (especially before 1915) were either eastern banks or

Jews starting movie studios. The dream was never more embodied than by the

glamour of Hollywood, which seemed

that even if not everyone could have the dream, it

could be captured forever in their imagination for the price of an admission

ticket.

Starr¡¦s

thesis presents simply that the two Californias, one

of fact and the other of dream, ¡§shape and reshape each other¡¨ the same way

Protestant high-mindedness coincided with the region¡¦s Catholic traditions.6

Because these elements both complemented and tugged at each other, they created

a natural forward evolution for the state. The concept of actually progressing

forward, Starr argues, is a byproduct of the personal goals of the great

individuals of California

who¡Xmore than movements¡Xcontributed to the growth of cities and regions. They

sought to build lives for themselves and in the process created the world

around them. With the ending of the Southern Pacific Railroad monopoly, not

only were other railroads allowed to prosper, but also those who utilized

railroads had greater freedom in choosing who transported their goods and for

what price.

Starr

in many ways writes on the conservative side of history; his devotion to the

power of the individual, relative focus on New Englanders, and generally

romantic tone all point his book away from the more New Left perspective of his

peers. By focusing less on the movements of women and minorities and more on

the development of the upper classes, the works of the Harvard alumni in

southern California, and the

patronage of the extremely wealthy for the development of the arts, Starr leans towards the conflict-less unity of consensus historioragraphy. Ultimately being a New Englander himself

contributed to Starr¡¦s focus on the ¡§protestant high-mindedness¡¨ of the Southern

California he pictures¡Xhe identifies with it. On the other hand,

he addresses the siege of California

by corporations, noting that by 1870 ¡§much of the land

of California had fallen into the

hands of a few individuals or corporations¡¨, thus Starr is not without gray

areas in his treatise.7

While

Starr is popular with consumer historians, literary critics certainly find

numerous grounds on which to lend their words. In a review by Raymond Starr of The Journal of San Diego History, Kevin

Starr¡¦s examination of California

and depth of knowledge allows for praise while his neglect of key issues

presents itself at the forefront. Raymond Starr argues that ¡§one gets the

feeling that the labor struggle is not Starr¡¦s favorite subject¡¨ as Starr never

mentions the great involvement of the Industrial Workers of the World and their

actions in the 1912 free speech movement.8 Many of the topics

concerning California¡¦s development had been covered in Starr¡¦s previous book

and thus, for one not reading the series as a whole, the development of

California¡¦s irrigation system and the general movement of water is shortchanged

considering its magnitude on the events and development of the state that is

not naturally blessed with water. Raymond Starr does, however, recognize the

skill by which Starr shows that the ¡§dream¡¨ of California

becomes sidelined by the ambitions of profiteers and is a byproduct of the

search for economic fulfillment rather than the progress of all. In short,

Starr¡¦s history is good, but his narrative has some plot holes.

Michiko

Kakutani of The

New York Times had a less favorable review for Starr. She states that Starr

¡§never quite pulls off the ambitious task that he has set himself¡¨ and that

instead of presenting a narrative that illuminates the dream the California

represents, Starr fumbles through disorganization.9 The chapter on

Arthur Page Brown and San Francisco architecture certainly was a departure from

the Southern California focus that the book was described as and simply should

have been in the first novel that encompassed more of Northern California.

Ultimately, she claims, the book is a cameo of ideas and characters that never

culminates in a cohesive vision and thus Starr set a goalpost he could not

conceive in actuality.

For

the most part Starr creates his vision but in many regards, does so

haphazardly. The chapters and overall flow of the book read disjointedly, at

times sacrificing flow for atmosphere and the addition of another anecdotal

rags-to-riches story to emphasize the mythos Starr himself enjoys. Also key is

Starr¡¦s predilection for the New England-intellectual sentiment. At times, the

addendum of another ¡§Harvard man¡¨ description of Charles Lummis

seemed at times superfluous and a less-than-subtle hint at a bias.10

However, this lean works two-fold; firstly, it hints at bias. Second, it

presents a key notion to Starr¡¦s thesis: that California¡¦s

dream was forged by eastern individuals. The saying ¡§it takes one to know one¡¨

applies very much here and aptly describes some of the more intentional slants

that present themselves throughout the book. In general, Starr creates a thorough

vision but steers clear of controversy and more risk-taking analyses of

history, instead favoring the road more traveled¡Xa sure fire, accessible

historical effort.

For

the most part, California seemed

to be a world unto itself and never dealt much with the events on the east

coast. Starr avoids delving into California¡¦s

involvement in the Civil War and the First World War, focusing on its

independent development. The sparks of California literature, however, are

attributed to post war movement west as Starr describes how ¡§for a brief period

after the Civil War, San Francisco was the literary capital of the nation¡¨.11

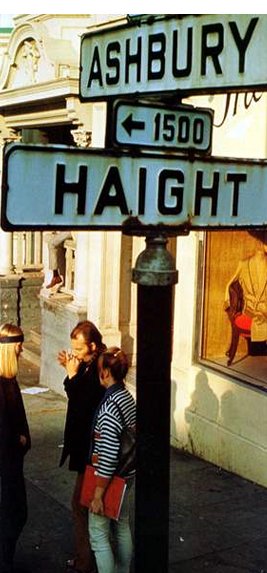

Instead of war and post-war evolutions, Starr focuses on California¡¦s

distinctness from the rest of the country in that it was an amalgamation of

ideas and traditions into a macro-culture. The synthesis of Hispanic

Catholicism and Anglo-Protestantism were good bedfellows in the cultural

bedrocks of the land, allowing for business with a certain ease. The flow of

California seemed to work the same way the Spanish conquered it¡Xbottom to top,

with Southern California often times leading the social revolutions of the

state and in the case of Hollywood, creating an economic titan.

Starr

describes California as the ¡§¡¥magic lantern screen¡¦ onto which [Americans¡¦]

national fantasies are projected¡¨.12 In this way, Starr portrays

California as the tangible final frontier, the land of milk and honey that

people ventured to, beginning their lives anew in search of health, wealth, and

general prosperity. With California

to the west, Americans had that hope of a future and life ahead of them. Hollywood

gave visions and dreams to the people, especially in times of doubt and helped

make the 20s roaring. Because of the magnitude of the California

experience, it was on the frontline of social revolution and led the way for

the rest of the country. Starr¡¦s ultimate argument summates as the ¡§city upon a

hill¡¨ notion of California¡Xone

that has since become shopping malls and suburbia.

Regardless

of the problems with disorganization or other trifles, one can fault neither

Starr¡¦s dedication nor his passion for the subject. To him, California

embodies the dream he writes about. If New Englanders are the descendants of

the stiff-upper lip traditions of old Europe, California was the fire and

passion that gave the United States contrast, if not only because it enigma was

enshrouded by the vast expanses that make California more analogous to a

country than a state. The people who came to California came out of a faith in

the notion of the ¡§search for a better life¡¨ and while many suffered the same

socio-economic adversity found around the country, others found the glory and

satisfaction of an individual success¡Xthe foundations of what progressed and

expanded the idea of California.13 While the dream may have been

lost to the reverse-subdivisions of suburbanism,

Hollywood still embodies the art and creativity that makes California that

center of inevitable attraction. Perhaps the journey pales to the importance of

the necessity to dream it.

1. Starr, Kevin. Inventing the Dream: California

Through the Progressive Era. New

York: Oxford

University Press, 1985. Page vii

2. Starr, Kevin 31.

3. Starr, Kevin 75.

4. Starr, Kevin 199.

5. Starr, Kevin 309.

6. Starr, Kevin vii.

7. Starr, Kevin 164.

8. Starr. Raymond. "Book

Reviews," The Journal of San Diego

History Fall 1985. 2 Jun

2008

<http://www.sandiegohistory.org/journal/85fall/br-inventing.htm>

9. Kakutani. Michiko. "Books

of the Times," The New York Times 13 Feb 1985. 2 Jun

2000.

<http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E04E5DC1439F930A2575 1C0A963948260&scp=1&sq=inventing+the+dream&st=nyt>

10. Starr, Kevin 76.

11. Starr, Kevin 31.

12. Kakutani, Michiko 1.

13. Starr, Kevin 339.